Non-Convex Optimisation Learning Rate Scheduling

One of the most crucial hyperparameters in any machine learning (ML) model is the learning rate. A small learning rate often results in longer training times and can lead to overfitting. Conversely, a large learning rate may accelerate initial training but risks hindering the model’s convergence to the global minimum and can even cause divergence. Therefore, selecting the appropriate learning rate is a critical step in training any ML model.

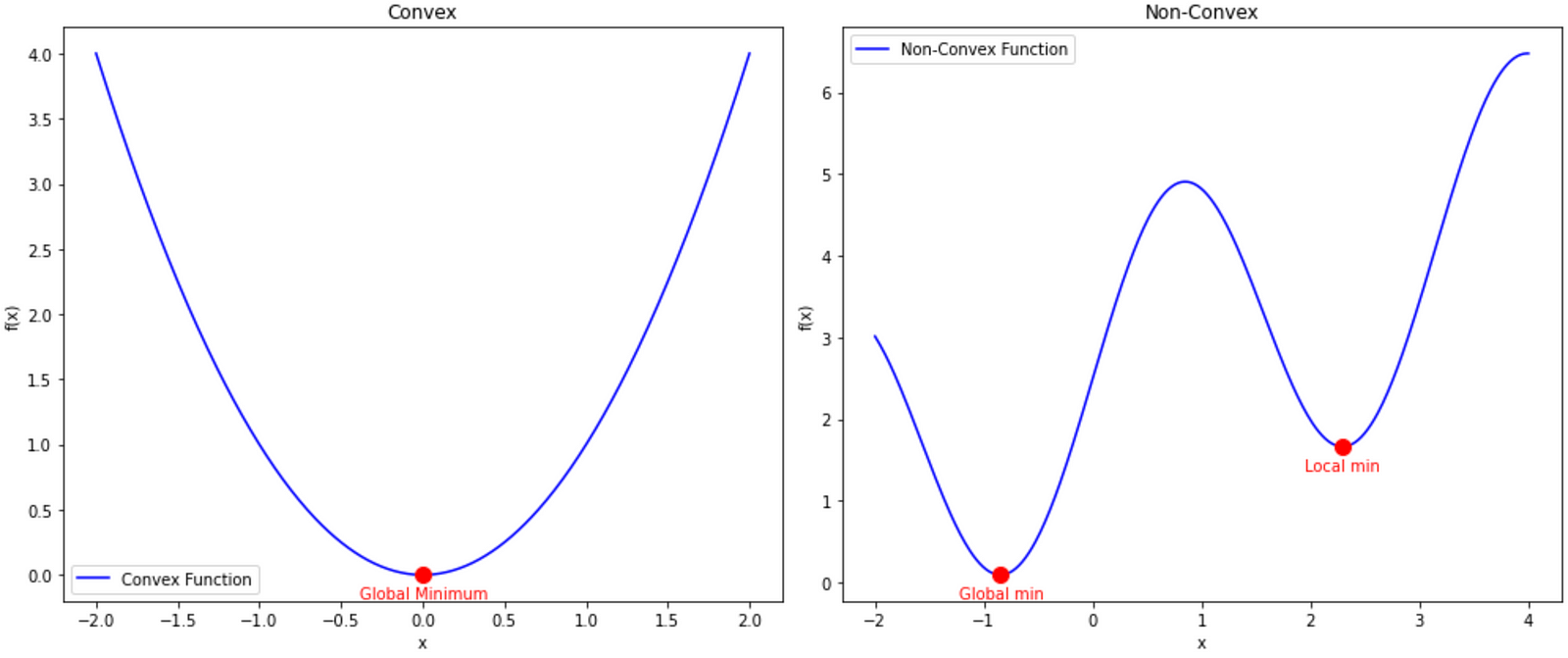

Over the years there have been a host of methods used to find the ideal learning rate with each of these methods tailored to different settings. This article will focus on the learning rate strategies in the non-convex optimisation setting. These non-convex functions are what’s hidden behind the of all Deep Learning (DL) models used today such as ChatGPT, Claude, AlphaFold, and many more models.

The objective in training any deep learning model is to find the parameters that best minimize the loss function. This requires finding the minimum of a non-convex function, which is challenging due to the presence of multiple local minima. Consequently, optimisation methods must be carefully designed to ensure convergence to a global minimum rather than getting trapped in a local minimum.

Fixed Learning Rate

A straightforward approach is to use a fixed step size, which often works well for simpler machine learning models like linear regression and logistic regression, where the loss function is convex. However, in deep learning, where models are typically non-convex, the training process can be much more unstable. As a result, a fixed learning rate is seldom sufficient in deep learning settings. Instead, a variable learning rate is almost always employed to better handle the complexities and instabilities of the training process.

Diminishing Learning Rate

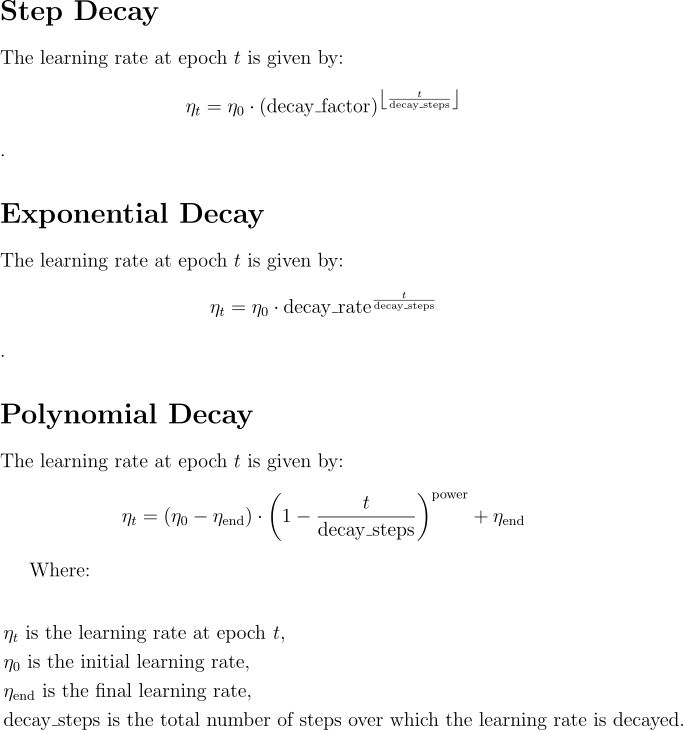

There are several strategies for applying a variable learning rate. One common approach is to use a diminishing learning rate, where the learning rate decreases according to a fixed schedule over time. Well-known methods for diminishing learning rates include step decay, exponential decay, and polynomial decay.

Starting with a high learning rate allows the model to explore the “loss landscape” more effectively, helping it to escape local minima and increase the likelihood of finding the global minimum. As the learning rate decreases over time, the model should ideally have explored enough of the loss landscape to identify the location of the global minimum.

Decaying learning rates have been successfully applied to optimizers such as SGD and momentum-based methods. However, they come with several limitations, including:

- A learning rate that decays too quickly can leave the model with insufficient time to thoroughly explore the “loss landscape,” potentially causing it to converge to a local minimum with a suboptimal loss.

- Additionally, decaying learning rates involve several hyper-parameters, and the learning rate can be highly sensitive to some of these parameters. Finding the optimal settings often requires extensive experimentation and tuning, which can be a time-consuming process.

- Moreover, these methods are inflexible because they do not adapt dynamically to the current gradient information during training. This lack of adaptability can hinder their effectiveness in some scenarios.

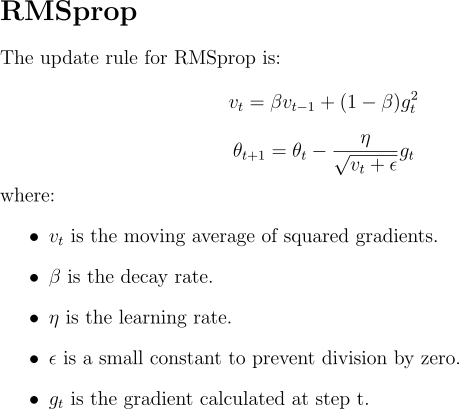

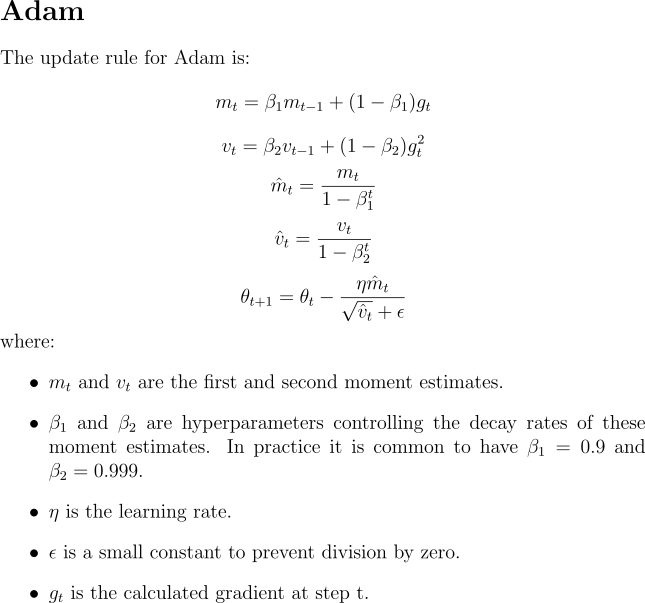

Adaptive Learning Rates

This leads naturally to the next group of methods: adaptive gradient optimizers. These optimizers adjust their learning rates based on the gradients observed during training, making them less sensitive to the initial learning rate. They adapt the learning rates dynamically by incorporating gradient information into the calculation of the current step size. Classic deep learning optimisers such as Adam and RMSProp are prominent examples of this category.

Each of these methods has its own advantages and disadvantages, which are beyond the scope of this discussion. However, it is highly recommended to explore these algorithms further, as they remain widely used in many deep learning applications. For instance, a variant of the Adam optimiser, known as AdamW, was employed to train the LLM model LLama3.

Cyclical Learning Rates

Another common approach involves Cyclical Learning Rates (CLRs). Unlike traditional methods that monotonically decrease the learning rate over time, CLRs oscillate the learning rate between a minimum and maximum boundary value. High learning rates in this scheme help the optimizer escape local minima and explore the entire loss landscape, while lower learning rates assist in fine-tuning.

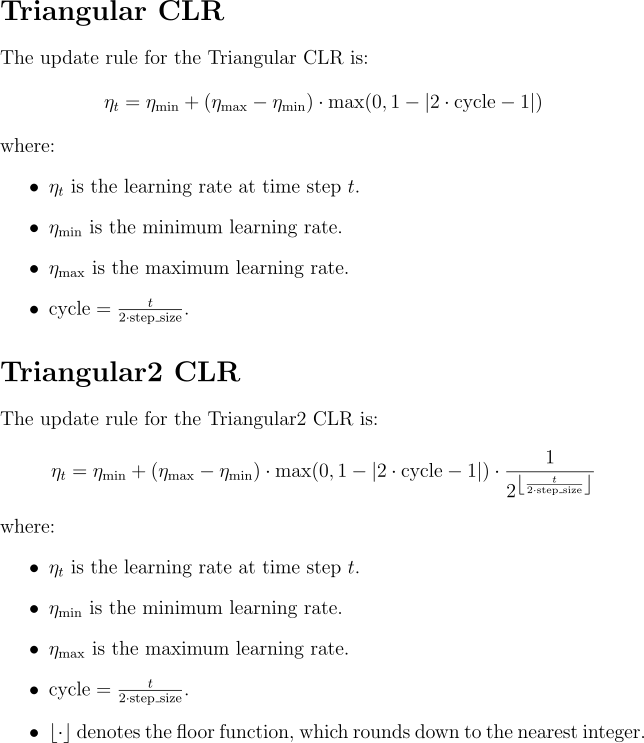

Determining the appropriate maximum and minimum learning rates is crucial when using cyclical learning rates. If the maximum learning rate is too high, the model may diverge, while a learning rate that is too low can result in slow convergence. To address this, CLRs are often paired with the Learning Rate Range Test (LRRT) to identify suitable boundary values. Additionally, incorporating momentum can help smooth out the oscillations caused by the high learning rates, enhancing convergence. Common CLR methods include Triangular and Triangular2.

To perform the Learning Rate Range Test (LRRT), start with a small learning rate and choose a maximum learning rate. Gradually increase the learning rate from the minimum to the maximum over a set number of epochs. By plotting the loss as the learning rate increases, you’ll typically observe a period where the loss decreases significantly before it begins to rise again due to the learning rate becoming too high. The minimum learning rate for CLRs is identified as the rate just before the sharp drop in loss, while the maximum learning rate is the rate just before the loss starts increasing again.

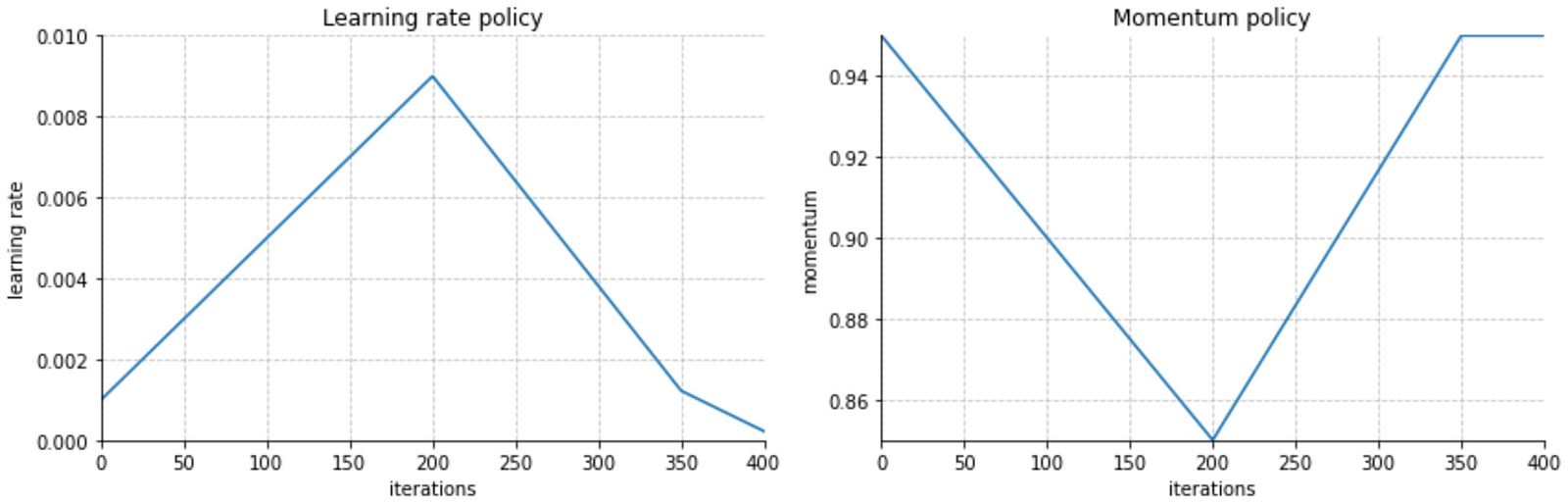

Cyclical Learning Rates (CLRs) were introduced by mathematician Leslie Smith and continue to be widely used. Smith also introduced other learning rate strategies, such as 1Cycle. Similar to CLRs, 1Cycle involves cyclic changes in the learning rate, but it uses a single cycle (hence the name). The 1Cycle method starts with a low learning rate to initialize training, gradually increases it to a maximum, and then decreases it to a value lower than the initial learning rate.

Momentum plays a crucial role in the 1Cycle learning rate strategy. It starts high and decreases as the learning rate increases, encouraging the optimizer to explore the loss landscape. As the learning rate decreases, momentum is increased to help refine the convergence.

Similar to CLRs, the 1Cycle method is sensitive to the choice of maximum and minimum learning rates, as well as the cycle length. To determine the appropriate learning rate range, the Learning Rate Range Test (LRRT) can be employed.

Conclusion

This article provided an overview of various learning rate strategies used in non-convex optimization, including diminishing learning rates, adaptive learning rates, Cyclical Learning Rates (CLRs), and 1Cycle.

There is no one-size-fits-all learning rate procedure; each has its own advantages and disadvantages. It is also crucial to recognize that the effectiveness of these methods can vary depending on the specific model, as each model’s loss landscape is unique. Therefore, some learning rate strategies may perform better or worse depending on the model they are applied to.

References:

- Smith, L. (n.d.). Cyclical Learning Rates for Training Neural Networks. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1506.01186.

- Smith, L. (n.d.). A DISCIPLINED APPROACH TO NEURAL NETWORK HYPER-PARAMETERS: PART 1 -LEARNING RATE, BATCH SIZE, MOMENTUM, AND WEIGHT DECAY. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1803.09820.

- Kingma, D. and Lei Ba, J. (2015). ADAM: A METHOD FOR STOCHASTIC OPTIMIZATION. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1412.6980.

- Ruder, S. (n.d.). An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms *. [online] Available at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1609.04747.